Every woman needs to know that her vagina has a sphincter. This sphincter muscle is called the bulbocavernosus (sphincter vaginae, in Latin) and very few people know about it. Including doctors.

If we all understood the bulbocavernosus muscle, there would be far less suffering in the world.

When your vagina’s sphincter is working fine, you don’t even know it’s there. And most people’s bulbocavernosus works fine most of the time. Without any effort or trouble. Until it doesn’t.

When it’s not working correctly, the bulbocavernosus muscle can cause vaginal sex to be painful.

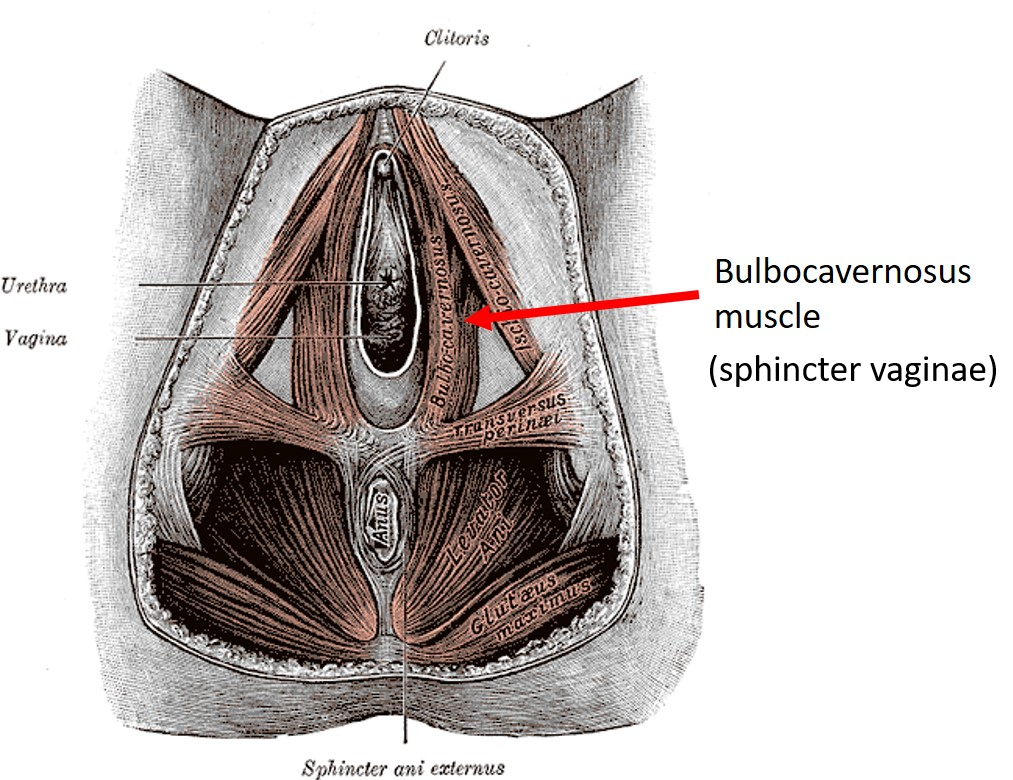

What causes this unfortunate condition? First, an anatomy lesson. The image below shows the muscle layer of the female vulva. Imagine a woman sitting in a wide-legged yoga pose with her feet pointing out to the sides. When we look between her legs (she has given us her permission), we are looking straight at her vulva. In the image, we see only the muscles of the vulva, which sit protected below layers of hair, skin and fat.

One way to understand the mysterious bulbocavernosus sphincter muscle is to think about another sphincter, which we all know well: the anal sphincter.

Most of us, regardless of age or gender, are well-versed in the workings of the anal sphincter muscle. When it’s working right, the anal sphincter is in a contracted state.

The definition of a sphincter muscle is a muscle that rests in a slightly contracted state.

This means that things stay put in the bowel until we are ready to let them out. When we do pass stool or gas, we “bear down on” or release this sphincter muscle to achieve the goal. Bearing down is a conscious act that overcomes the normal, contracted, closed state of the anal sphincter. We bear down using a trick of physiology called a “valsalva” maneuver to generate enough pressure from inside our body to overcome the pressure in the anal sphincter muscle.

In its resting state, like when a woman is walking her grandson to school or giving a lecture or driving a truck, this bulbocavernosus muscle is also somewhat contracted.

So a bulbocavernosus muscle is not dysfunctional when contracted. It’s normal to be that way and it’s doing it’s job. It’s not right to call this muscle uptight or dysfunctional.

Unlike the anal sphincter, the vaginal sphincter is not really holding anything in. In a woman with incontinence (including urinary, stool, or gas), or with vaginal prolapse, the bulbocavernosus can subconsciously tighten up as her body “recruits” this muscle to help keep things from coming out. Our truck driver friend who really has to pee on a long haul might squeeze her bulbocavernosus muscle in an effort to “hold it” until she gets to the next truck stop.

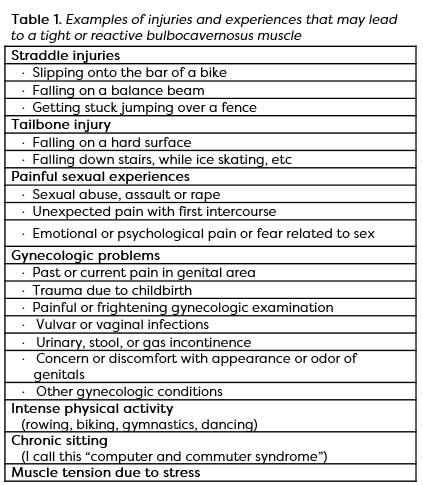

Women who have a history (recent or long ago) of physical and even psychological trauma involving the genital area can also develop excess tightening of this muscle, without realizing it (see Table 1).

In some women, the muscle stays tight all or most of the time—even when it shouldn’t be. It can become so tight that even the most determined signal from a woman’s brain is not able to release it– even when she desires to have vaginal intercourse with her partner. Or, it can tighten up on occasion, like when a woman is thinking about or attempting to have sex or have a gynecologic exam. For some women, it’s situational. The bulbocavernosus might work fine during sex, but contract up for a gynecologic exam. Or, it might work fine in the doctor’s office, and tighten up during sex.

A tight bulbocavernosus muscle is most noticeable during attempts at vaginal penetration. The word to describe tightness in this muscle is “vaginismus.”

When vaginismus happens, the muscle is not the only problem. The muscle squeezes the small blood vessels, depriving the area of oxygen, and it squeezes the small nerves which can be painful.

In women without much estrogen due to menopause or anti-hormone treatments for cancer, the tightening of this muscle can pull the whole vagina tight. This makes it feel like the vagina is shorter and narrower. A really tight bulbocavernosus can even trigger tightness in the other muscles of the pelvic floor, making the blood flow and sensation necessary for sexual arousal and orgasm more difficult.

Kegel exercises, which are meant to strengthen loose muscles in the pelvic floor, are not an effective treatment for vaginismus. Muscles can be weak when they are too loose (this is when Kegel’s may be helpful) and muscles can be weak when they are too tight (this is when Kegel exercises are NOT helpful).

Before you decide that you need to do Kegel exercises, have a doctor examine your pelvic floor muscles and advise you.

The absolutely predictable thing a woman with vaginismus will tell me about her attempts at vaginal penetration is:

- “it feels like there’s a wall in my vagina” or

- “my partner feels like they are hitting a wall” or

- “my tampon is hitting a wall and I can’t get it in.”

My patients with cancer (and even some without) sometimes tell me they are worried this wall is actually a cancerous tumor blocking up the vagina. Women without cancer might imagine that they have some kind of birth defect. While it’s not impossible, I’ve never once found cancer or a birth defect as the explanation for this problem. I make sure to tell everyone that, because I’m sure many more women worry about it then actually say so.

Then I ask, “how far in your vagina do you feel this wall?” And my patient uses her thumb and index finger to show me, without fail, a distance of about 3-4 centimeters. I tell her that this is just about the thickness of a tightened bulbocavernosus muscle at the opening to her vagina.

Vaginismus is a very common problem and most women experience an unexpected tightening up of this muscle at some point in life. Luckily, with a little practice, anyone can learn to understand and appreciate their bulbocavernosus muscle. This understanding can increase your control over this muscle during sexual penetration, tampon insertion, and gynecological exams, and even give you joy! Mystery solved! Knowledge is power!

Intrigued? Click here for Part 2, where I’ll tell you how to get to know your bulbocavernosus sphincter muscle.

Edited by Chenab Navalkha, Gillian Feldmeth, & Kelsey Paradise